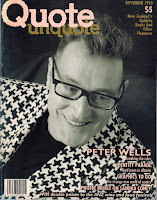

To mark the death of writer and film-maker Peter Wells on

Monday, the 103rd in this occasional series of reprints from

Quote Unquote the magazine is from the fourth

issue, September 1993. The photograph and cover shot are by Simon Young: this

was possibly the first time a mainstream New Zealand magazine sold in

supermarkets had an out gay man on the cover. The intro read:

The Piano wasn’t

the only New Zealand film to make a big splash at Cannes this year. Desperate Remedies, directed by Peter

Wells and Stuart Main, was in the prestigious “un certain regard” section and

sold spectacularly well around the world, including the all-important US

market. But the Film Commission wasn’t so enthusiastic, at one point deciding

that the film shouldn’t be made. Stephanie Johnson talks to Wells about his

sensuous fairy-tale.

BREAKING THE RULES

In the last decade Peter Wells and Stuart Main have made a

number of remarkable short dramas and documentaries, including Jewel’s Darl (based on a short story by

Anne Kennedy) and A Death in the Family,

which won awards here and in the US and Canada. Their first feature is the

startling, sensuous and liberating Desperate

Remedies.

Wells is also a successful writer of fiction. His short-story

collection Dangerous Desires picked up

the Reed fiction award and rave reviews at home, and will soon be published in

the US, with potentially lucrative sales to the large gay market there.

Main loathes being interviewed, so while his shadowy

presence lurked about their lovely Ponsonby villa, I talked to Wells in his

study, from which you can see the glinting harbour and the puffing chimneys of

the Chelsea sugar works.

SJ: What are the logistics of co-directing?

PW: People always

ask about the co-directing. It’s not as strictly demarcated as one of us

directing the camera crew and one of us directing the actors. The film can

break up in different ways — like in this film-I worked more with Lisa Chappell

[who plays Anne Cooper] and Cliff Curtis [as Fraser].

What a find! He was

wonderful. Such a decadent face. Had he done much work before?

A bit. He just appeared out of the blue. Watching him last

night [at the premiere], I think he’s the first Maori actor we’ve seen on film

who isn’t self-conscious.

The common wisdom is

that co-directing can’t be done.

Because Stuart and I have been it for quite a long time it

crept up on people before they could make a judgment. In some of the films

we’ve made together I’ve directed, Stuart’s been first assistant director and editor.

In other films I’ve been writer and set director and he’s been director.

I suppose you and

Stuart had the odd disagreement?

Yes, we would’ve. I suppose with this film Stuart was much

more remorseless than I was in terms of style.

But you were remorseless

about the actors keeping to the text?

[He laughs] With the partnership, people are always

fascinated by the technical processes of it. I think it’s allowed both of us to investigate all

sorts of areas which individually would have been very difficult to have

brought off. Like creating a kind of queer cinema. Because we've been able to

do it together there’s been support and a kind of push/pull relationship.

I think if we’d been doing it individually, almost

inevitably we would’ve gone overseas. As it is we’ve created our own sort of island,

and now there’s Garth Maxwell and all sorts of other people, and so it gets

bigger and bigger. That’s been the most creative aspect of the partnership.

Who yells out

“Action”?

Stuart does normally. But we talk a great deal before we begin

the project. We do quite a lot of rehearsal, an unusual amount for film. With Desperate Remedies, as with Death in the Family, we did our

rehearsals with a video camera there, so we were planning our shots at the same

time. It’s: only in rehearsal that you start to discover what you’re doing.

Desperate Remedies is such

a vision — it has such a look — that I wondered how you’d arrived at a vision

like that together.

It was worked out really with Stuart, me, Michael Kane and

Glenis Foster, who are the set and costume designers. We’d sit down in this room

and we’d talk forever. The basic starting point was we didn’t have a big budget

so we could be as extreme as possible.

How much did it cost?

$2.1 million. In terms of international budgets it’s tiny.

Do you think the costs

of it were kept down because it was shot indoors? If you’d actually gone down

to the wharfs, you would have had to dress them and park a sailing ship there.

We’d decided we didn’t want that kind of film.

There were jokes in

that scene that I think only New Zealanders or possibly people from colonial

countries would appreciate — from both sides of the fence. Like “Natives No

Problem" on a placard.

New Zealanders will have different readings of the film to others.

People have said to me it doesn’t have any point of view of history, and others

say it’s revisionist. I see the film as an escape from history, although it has

a point of view on history.

When I was doing research I read about a family who lived in

New Plymouth at the time of the land wars. They were such desperate times then,

when people had to withdraw into a stockade and their houses were burnt down and

they lost absolutely everything. They had to stay in the stockade and try to

eat whatever was in the cupboards, and then when that disappeared and they were all sleeping in a

room, it was all sort of desperate. And it really appealed to me as a

philosophical territory. Desperate Remedies

is not as desperate as that, but we wanted the feeling of a stockaded town where

everyone’s pushed in and so people are going to do all sorts of things, even though

it’s all sort of exaggerated and mad and wild.

I would call the film a queer take on Mills and Boon. Stuart

and I as little poofters growing up loved all that sort of Mills and Boonie

historical romance kind of thing. A lot of the pleasure came from the fact we were

able to take Historical Romance — the great heterosexual genre — and change it around

so that what is always meant to be the great ending is subverted.

The language in the

film is striking, archaic in a way. Like “those who light the fuse may live to

be blinded by it”.

I enjoyed writing that dialogue. I worked with Debra Daley

on the second draft. She was the script editor. We had a great deal of fun with

that duelling dialogue. You don’t really know what anyone is thinking, but

they’re duelling back and forth all the time.

The high-flown nature

of the film is so refreshing. In New Zealand we still seem to believe that you

don't blow your own trumpet — you make films about what you know about, your own

life’s experience. It’s a death of the imagination.

It was a very easy screenplay to write even though it took

five years. But the five years were really spent in the politicking.

The Film Commission

asked you not to talk to anyone at Cannes about how they’d first knocked you

back. What was the story there?

If something like this comes along, which is out of the

context of all the films that have been made up to that time, of course it’s

high risk. I’m so pleased we’ve got a Film Commission, and it’s absolutely

essential that we do, but the voting situation on it is a strange one whereby

there are always producers and directors on it. In a way, whatever project

comes, it has to be fitted within the profile of their own projects. If your

project comes up at the same time as one of theirs . . .

We went through a terrible stage when they’d spent something

like $70,000 developing the script. We were going for production money and they

said no, we’ve decided this film can go no further, it’s not on, it won’t work.

So we just had to say you’re wrong, it’s going to be made. I talked last night

to the people who said this film won’t work and they said, oh, we didn’t

understand the way you were going to make the film.

Was it the style of

the film that confused them?

I think so. In a way we also had to educate a lot of the

actors. Stuart and I grew up in a time when on television there were a lot of

old films on a Sunday afternoon, so you grew up almost unconsciously learning a

history of cinema. These days the films are on at such terrible times nobody

watches them, so everybody loses that history. So we sat down with the core

cast, the six main actors, and we watched those fast-talking films of the 30s and

40s. Something that’s been lost is the speed at which people talked, the way

they cut in on each other. When they watched them they suddenly clicked into

the type of performance we wanted from them. In a way it was quite liberating

for them to actually be bravura and to be able to walk right up to a camera.

There are lot of close

ups. They’re all such beautiful people.

That’s part of the language of the melodrama genre. All the

main characters are incredible-looking and all the extras are character faces.

Everyone who isn’t part of the main drama is a kind of character face that you

can read at a glance.

I kept thinking it was like a fairy-tale too. The

opium-smoking caterpillars reminded me of Alice

In Wonderland. [He laughs] I think it’s a fairy tale in both senses of the word.

Because you’d

rehearsed the actors such a lot, how many takes did you do, on average, for each

scene?

It varied. Not many with Jennifer [Ward-Lealand, who plays

Dorothea].She has an almost faultless technical ability. It was interesting

working with Jennifer and, say, with Cliff, because they were so different in

their approaches and they challenged each other. Cliff is such a method sort of

actor. He would charge all over the sets working himself up into a complete lather

before a take.

Had Anne and Dorothea

escaped so they could be lovers here without the eye of England on them?

They had no relation to England, really. Calling her

Dorothea Brooke was a totally conscious thing. She’s the heroine of George

Eliot’s Middlemarch. In a way we wanted

to take a certain kind of Victorian independent woman of sensibility and place

her in a quagmirey colonial situation.

The house that she

lived in was extraordinary, with all the reflected surfaces and the feeling that

at any minute it was all going to shatter.

They were the first scenes we did, the drawing-room scenes.

It was wonderful for the crew and cast, because the first rushes we got back

looked so staggering. We were all on a complete high.

I’ve never seen a New

Zealand film as sumptuous as this. I remember after seeing it feeling relieved,

as if a barrier had been broken and we were at long last allowed to make films

that don’t have all the way through them: “This is a community announcement.”

Making such a theatrical film is a good thing, because I think

New Zealand actors on the whole have had to be very throttled in their kind of emotional range,

more throttled than New Zealanders actually are.

Is that possible? Now,

the other thing I wanted to talk about is the music. It really stands out, it’s

one of the aspects of the film you remember.

Peter Scholes composed the score. He did a wonderful job.

Music is another part of the language of that genre. We used the Auckland

Philharmonia — 70 pieces, right down to a wonderful Russian violinist.

Writers who want to

write films have got to deal with the fact that film-makers have often got such

literal minds. It’s such a struggle that in the end many good writers think, I

can’t be bothered, I’ll go and write a book.

For me as a writer I really like the fact that I’m involved in

the film world. I notice for some writers that they see it as some form of

prostitution. I think it’s a good combination to have. Financially it makes

your life so much more possible, because writing for film brings in a lot more

money. There are also craft considerations with whatever you’re doing. When I

go back to writing fiction I find it very pleasing because it seems so limitless.

Have you started

another screenplay yet?

I’ve got two I'm slowly working on. The ideas are just

forming. I had a lovely conversation with Shonagh [Koea] about the rituals of writing.

You know, how it’s such an important thing to have a routine and a rhythm.

I really underestimated how easy it would be to go from

doing a film back to fiction. I just thought, oh we’ve finished, I’ve had a holiday

now, so I can sit down and work. I’ve got back into that way of thinking that it’s

a lucky thing, even though at times it feels like hell.